115. SAFETY LAST, 1923

- Jay Jacobson

- Dec 13, 2022

- 16 min read

A thrilling comedy that will leave you laughing and gasping in awe

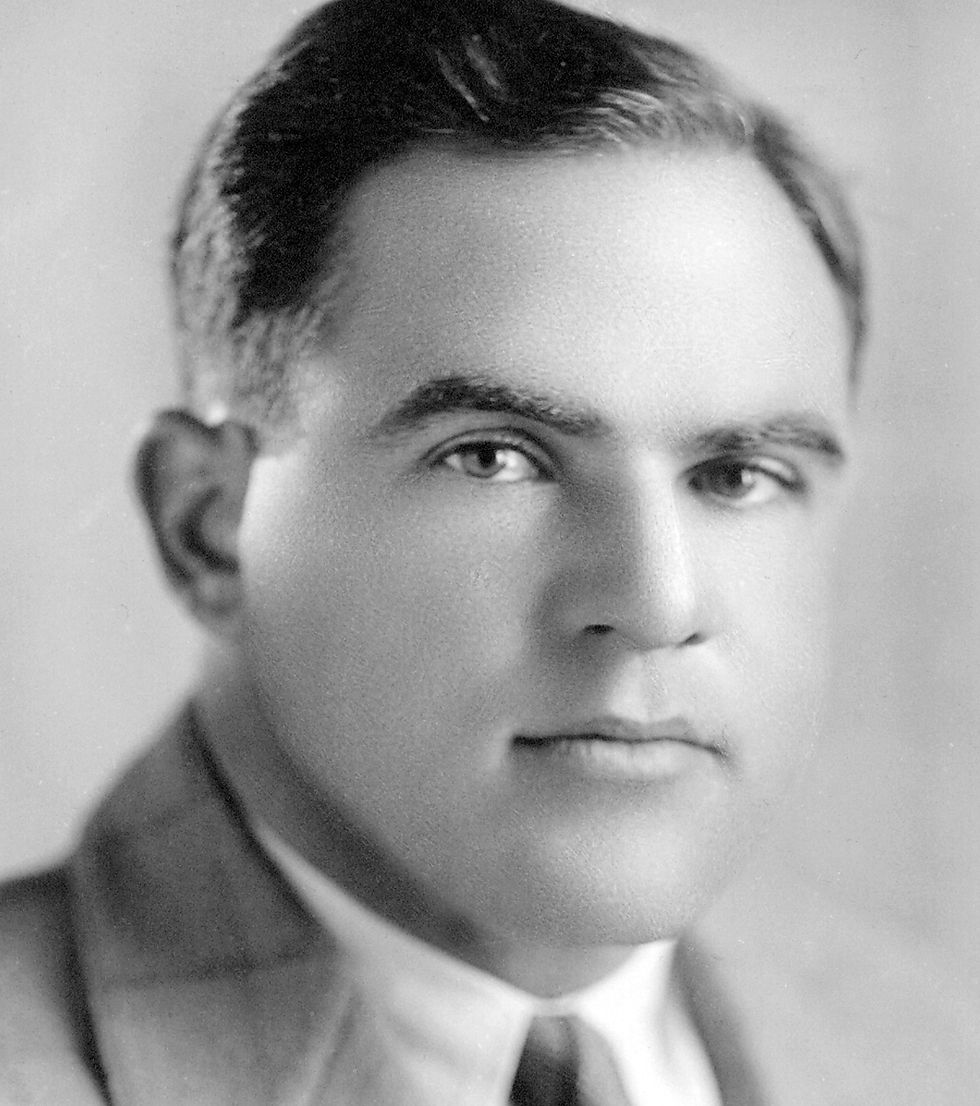

When something is truly entertaining it remains timeless. If one needs proof, a single viewing of this week’s classic film “Safety Last”, will amply do the trick. This jewel of a film is chockablock with enough riotous visual gags, mind-blowing physical stunts, and hair-raising thrills to produce audible laughs and gasps from an audience of any age at any time. It was spearheaded by one of the geniuses of film comedy, Harold Lloyd, and though his name may not be as well known today as his contemporaries Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, in his day, Lloyd matched and even surpassed them in popularity and box-office receipts. Filmed 100 years ago, this silent gem holds up so well that in 2001, the American Film Institute (AFI) named it the 97th Most Thrilling American Film of All-Time. And it’s so packed with comedy and daring feats that I find new laughs and marvel at it each time I watch it.

Though dolled-up with funny jokes and outrageous situations, at its core “Safety Last” is a romantic comedy with a very simple plot: a country boy wants to marry a country girl and feels he must prove himself a financial success before they wed. He goes to the big city and finds work as a clerk selling fabrics in a department store, and the girl mistakenly comes to believe he is the store’s General Manager (mistaken identity is a common theme in Lloyd's films). The film shows the crazy lengths to which he will go to save face and still get the girl, culminating in a heart-stopping climb up the face of a skyscraper. The approximately twenty minute climax is one of cinema’s most famous sequences, and its image of Lloyd hanging from the hands of a clock is one of the most iconic in cinema history.

It’s important to note that this film was made in the 1920s – an era of the daredevil. Being shot out of a canon, sitting atop flagpoles, climbing buildings, stunts on the wings of bi-planes, and crashing planes and cars were just some of the feats that thrilled audiences at the time. Lloyd himself had made three previous short films, "Look Out Below" (1919), "High and Dizzy" (1920), and "Never Weaken" (1921), which became known as “thrill pictures". In them, he did daredevil physical feats, combining laughter with fear.

“Safety Last” became the ultimate thrill picture. Its characters and plot were more intricate and stunts more outrageous than in any previous thrill picture. Reportedly people screamed in fear and some even fainted while watching the film, and one article’s headline even read, “'Safety Last' Liable To Cause Heart Failure”. The film's length (the first feature-length thrill picture), perfect comedic timing, ample emotions and complexities refined and elevated this unique type of comedy to new heights (so to speak). It was such a hit and so original that it cemented Lloyd as one of the biggest and most influential film comedy stars of the silent era and immortalized him as the face of the thrill picture (even though he only made five of them in his prolific career).

Lloyd was one of three undisputed comic geniuses of the silent era, the others being Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. In addition to making people laugh, they each pushed the boundaries of film and expanded the ways to visually tell a story. Though different, they had a lot in common. Each had flawless comic timing and a physicality that made pratfalls and acrobatics look easy, painless, and natural. They all began in short films and as they gained more stardom, began making features. In addition to starring in their films, at their height, they each had complete control over their films, and as a result, their bodies of work each have distinct personalities (you can read more about Chaplin in my post on “City Lights”, and Keaton in my “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” post).

While the three funnymen were all hysterically entertaining, their comedy couldn’t be more different. Chaplin played a vagabond known as “The Tramp”, and his comedy is flooded with poignancy and an innocent, romantic spirit. Keaton’s laughs grew out of his unmatchable physicality, his deadpan look, and his technical filmmaking wizardry. Lloyd’s humor evolved from the ordinary. His bespectacled character was a shy go-getter always trying to “make good”. He didn’t look like a clown or comedian, but like a typical guy of the 1920s who found himself faced with problems he’d have to use his smarts to solve.

Perhaps to keep audiences feeling he was an "everyman", his character was often listed as “The Boy” in the credits and referred to as “Harold” in the films (or as “Harold Lloyd” in “Safety Last”). It blurred the edges between Lloyd’s screen character and Lloyd himself, and the two would be forever mingled in the mind of the public. Chaplin and Keaton were almost always credited as the directors of their films, and though Lloyd never took a director’s credit, he was in charge and had final say (it’s often been said he directed his directors). Gag writers, directors, cameramen and so on, would run ideas past him which he would hone and refine. Lloyd appeared in more films than Chaplin and Keaton combined, and became one of the most popular and wealthiest men in the movies. I remember talking to my grandmother about Chaplin, and she said of the comedians of her day, "Harold Lloyd was my favorite".

Lloyd got the idea for “Safety Last” while walking in downtown Los Angeles. He happened upon a crowd watching “Human Spider” Bill Strother climb the face of the Brockman Building. After Strother rose about a third of the way, Lloyd became so afraid he had to walk away, but kept peeking back to see if this “Human Spider” made it to the top (which he did). From his own reaction and that of the crowd, Lloyd knew he had to put that stunt into a film and the rough idea for “Safety Last” was born. The film’s climatic climb was filmed first, and the rest of the story and entire lead-up were conceived and filmed afterwards. Let me point out that this was well before special effects, and all stunts in the film were real and dangerous. I’ll talk more about the building climbing in particular in the TO READ AFTER VIEWING section at the end for after you see the film.

An aspect I love about “Safety Last” (and many of Lloyd’s films) is that it was largely filmed on location. As such, it offers a rare glimpse of 1920’s American life. Shot on the streets of downtown Los Angeles, it shows authentic storefronts, transportation, traffic (before traffic lights), how people dressed, and a bit of insight into how they lived. Much of the film was filmed inside an actual Los Angeles department store, and we get to see the clothes, mannequins, display cases, elevators, soda fountain, and the social norms of the day. The protagonist is in danger of being fired because his shirt sleeves were showing, which could cause "shock to your customers”. Boy how times have changed.

On the downside, the film does contain a couple of offensive stereotypes, particularly that of a Jewish pawnbroker. As I’ve stated many times in this blog, these films are in a sense historical documents of the times in which they were made, giving us insight into where we came from, how far we’ve come, and how far we need to go. That's how we learn from history. As such, old movies can't be expected to live up to today’s awarenesses.

Because it overflows with fast paced comedy and thrills, it is easy to miss the impeccable artistry behind “Safety Last”. The film opens with a wonderful visual gag which is funny because of the camera placement. And the camera is used to full effect throughout the entire film, showing us everything we need to further the plot and add comedy. Another beautiful example is the entire sequence when "The Boy" is at the pawn shop buying a chain. The scene brilliantly uses shots and editing to show his dilemma of buying the chain and its ramifications. The film often uses long takes in which gags unfold, as well as the use of the iris and double exposures to heighten emotion and humor.

Under Lloyd's watchful eye, “Safety Last” was co-directed by Fred Newmeyer and Sam Taylor. Newmeyer had previously directed Lloyd in some short films, and would direct or co-direct Lloyd’s first eight feature films. Along with his work with Lloyd, actor/director Newmeyer is best known for directing some of the "Our Gang" comedy shorts, and directed 59 films (mostly silents), others of which include "Fast and Loose", "Girl Shy", "A Sailor-Made Man", "The Freshman", and "Too Many Crooks”. He also appears in "Safety Last” as the man who pulls up in a car next to the trolly and gives “The Boy” a ride. Fred Newmeyer died in 1967 at the age of 78. Sam Taylor was a director/writer/producer who, along with his work with Lloyd, was best known for his work with Mary Pickford, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. He directed seven of Lloyd's feature films, beginning with "Safety Last” and including "Girl Shy", "The Freshman", and "For Heaven's Sake". Other films of the 23 he directed include "My Best Girl", "Kiki", and his final, "Nothing But Trouble” in 1944. Sam Taylor died in 1958 at the age of 62.

Nebraska-born Harold Lloyd caught the acting bug at about nine years old, while appearing in a bit part in a one-night production of “Macbeth”. His parents divorced, and when his financially struggling father came into some money, he and Lloyd decided to start a new chapter in their lives and move to either New York or California. With bags packed, they flipped a nickel. If it landed heads side up it would be New York City, tails up, San Diego. Tails up it was. Set on becoming a stage actor, Lloyd studied acting in San Diego and appeared in various stock companies and acting troupes. With no intention of a movie career, he made his first film appearance as an extra in the Thomas Edison Pictures 1913 short film “The Old Monk’s Tale” solely for money. Facing financial troubles, he and his father moved to Los Angeles, and still having difficulties finding work, Lloyd tried again to get movie extra work. Finding it impossible to even be seen, he noticed that those in make-up could walk past the gateman at the Universal Film Manufacturing studio since they looked like they were in costume going to work. So he donned make-up, walked past the guard, managed to get work, and made a point of speaking to the guard on his way out (eventually not needing to wear make-up to enter). Lloyd’s resourcefulness and determination would soon catapult him to stardom.

At Universal, Lloyd befriended another actor working as an extra, Hal Roach, and the two learned how to make movies while working there. Roach came into a small inheritance and decided to form his own production company, and the first person he hired was Lloyd as the company’s comedy star. Because Chaplin was the biggest thing in comedy at the time, many screen comedians imitated his “Tramp” character, and Lloyd was no exception. The first character Lloyd and Roach created was “Tramp” inspired “Willie Work”, who unfortunately would have more appropriately been named “Willie Don’t Work”, because he wasn’t funny and nearly bankrupted the company. Roach and Lloyd briefly parted ways, and Roach began producing and directing at Essay Film Manufacturing Company while Lloyd worked for famed slapstick comedy producer Mack Sennett at the Keystone Film Company. As fate would have it, the successful film distributing company Pathé offered Roach a contract as long as he used the stars from his 1915 “Willie Work” film “Just Nuts” (which included Lloyd). At Pathé, Roach and Lloyd set out to create a new comedy character and came up with “Lonesome Luke”.

“Lonesome Luke” was another Chaplinesque character with funny shoes and a mustache, though where Chaplin’s “Tramp” donned large baggy clothes, “Luke” wore smaller, tight-fitting apparel. Roach directed the comedy shorts and the two would shoot these films based around an initial comedy gag, go on location in Los Angeles and make the rest of the film up on the spot. They relied a lot on physical comedy, which Lloyd mastered while working at Keystone. “Luke” became a popular moneymaker. But after about two dozen films Lloyd tired of the character. He reflected years later, “I had the feeling that I would never get any farther with ‘Lonesome Luke’ that I had, because underneath it all, he was a comedy character that couldn’t possibly rise to the heights that Chaplin had. And in some ways, while you didn’t try and imitate Chaplin, he was a character that dropped into that character”.

Lloyd then set out to create a new character and took inspiration from seeing an actor wearing a pair of horn-rimmed eye glasses without lenses. It gave him the idea for a character (though Roach later claimed he was the one who thought of the glasses - no one seems to know for sure whose idea it was). After choosing the exact shape and size (they were tortoiseshell), the glasses transformed Lloyd into what was a completely fresh and unusual character at the time, particularly for a comedian. In the fabulous book “Harold Lloyd: Master Comedian” by Jeffrey Vance and Suzanne Lloyd (Lloyd’s granddaughter), Lloyd explains, “While my character was not a comic character in appearance, I donned the glasses to make him instantly recognizable. They were not just a gimmick. They were a trademark, the same as Chaplin’s derby and cane. But my glasses gave a character besides. Someone with glasses is generally thought to be studious and an erudite person to a degree, a kind of person who doesn’t fight or engage in violence, but I did, so my glasses belied my appearance. The audience could put me in a situation in their mind, but I could be just the opposite to what was supposed. So the glasses not only had an identifying characteristic but also a comedy characteristic”.

Unusual and daring for the time, the “Glasses Character” (as he was called) looked like a real person, and Roach wasn’t keen on ditching the financially prosperous “Lonesome Luke” for a whole new untested character. He insisted Lloyd alternate between the two characters from film to film to see if the “Glasses Character” would be a success. Lloyd did, and as the “Glasses Character” became more and more popular, the “Lonesome Luke” character found himself retired after the 1917 film “We Never Sleep”. All “Lonesome Luke” films were eventually withdrawn from distribution and Lloyd bought the prints and rights to all his films distributed by Pathé and those made for Roach. He kept them in a vault in his estate and tragically in 1943, almost all of the “Lonesome Luke” films and negatives were lost in a fire.

In 1919, while doing a publicity photo shoot for the film “Haunted Spooks”, Lloyd picked up off the prop table what he thought was a fake bomb, lit it, and lit his cigarette with it. It exploded. By sheer luck, he had lowered the bomb away from his face just seconds before. The cameraman and prop director were both seriously injured, and Lloyd suffered burns on his face and chest, lost his thumb, forefinger, part of the palm of his right hand, and went blind. It looked like Harold Lloyd’s career was over. Luckily, the vision in his left eye came back three months later, and six months after that it returned to his right eye. Once healed, he insisted on returning to the screen and had a prosthetic glove made to look like a real hand. The glove fit over his entire right hand and contained a prosthetic forefinger attached to his middle finger (which moved with it) and a false thumb. If you look closely in his post-accident films you can see he is wearing a glove in some shots, but it is not easily spotted.

In 1921, Lloyd moved from making short films to comedy features beginning with "A Sailor-Made Man”. In doing so, he realized that unlike shorts (which could consist of comedy gags strung together with a quick storyline), to hold an audience’s attention during a feature-length film, it would have to be driven by a character with whom audiences could identify. He began to infuse the “Glasses Character” with personality and depth in his second feature, “Grandma’s Boy” in 1922, which revolutionized comedy. Under all the laughs was drama. His fresh approach to integrating comedy, plot, and character were enormously influential and helped usher in a new kind of comedy feature. The film’s praises were sung by both Chaplin and Keaton, and one can see its influence in their works. Lloyd was becoming a comedy giant, and his fourth film, “Safety Last” cemented his status as a worldwide star bigger than Chaplin and Keaton. He made enough money from “Safety Last” to start his own production company, The Harold Lloyd Motion Picture Company, and amicably parted ways with Roach. Producer/director/writer Hal Roach would come to be recognized as one of a handful of major forces in silent film comedy. In addition to launching Lloyd, he also paired together and produced the films of the legendary comedy team of Laurel and Hardy, created and produced the “Our Gang” (also called “The Little Rascals”) short films, and many of the films of the very popular comedian Charlie Chase. Hal Roach died in 1992 at the age of 100.

Lloyd was now in total control of his films. He bought his older films from Roach and from here on in, would own the negatives and rights to his films. Two films later came 1924's “Girl Shy”, the first production under his newly formed company. In 1925 came "The Freshman", which became his most popular film to date, firmly establishing the “Glasses Character” as an everyman. The hits "For Heaven's Sake”, “The Kid Brother”, and “Speedy” followed, and in 1928 he was named the highest-paid film actor of the decade and the world’s most popular comedy star. Truly an innovator, many credit him with inventing the use of previews to see how an audience liked or didn’t like a film before its initial release (he used them as far back as 1919). He would secretly sit in the audience and watch how they reacted (if they laughed, if they didn’t, when they laughed, and so on). And being in control of his work, he could then go back and reshoot, rewrite, or reedit if he felt it was needed.

Lloyd’s first sound film was “Welcome Danger” in 1929, which wasn’t well-received but still made money. It was followed by his first box-office disappointment, 1930’s “Feet First”, a thrill picture with sound. As the 1930s progressed, his somewhat carefree "Glasses Character" began to feel out of touch with Depression Era audiences, and rather than make a film or two a year, he slowed to one film every two years or so. The last film produced by his production company was "The Cat's-Paw" in 1934. Slowly giving up control over his films, with "Professor Beware" in 1938, he was involved only as actor and partial financier. Preston Sturges was a huge fan of Lloyd’s, especially his film "The Freshman", and urged Lloyd to appear in a sequel to be written and directed by Sturges called "The Sin of Harold Diddlebock" in 1947. Sturges and Lloyd did not get along, the film went over budget and over schedule, and was not well received. Its producer, Howard Hughes, re-edited the film and rereleased it four years later as "Mad Wednesday", but it failed again. Lloyd sued Hughes for damaging his reputation and settled for $30,000. Lloyd retired from movies.

After retiring, Lloyd directed and hosted a radio show, was involved with a number of charities (including as a Freemason and Shriner with the Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children), painted, occasionally appeared on TV talk or game shows, and took up 3D photography (including taking photos of Marilyn Monroe and Bettie Page). In 1952, he was awarded an Honorary Oscar for his work as a "master comedian and good citizen". As television began airing old movies, Lloyd did not grant the rights for his films to be shown (he didn't like the idea of commercials breaking the rhythm of the comedy), and largely because of that, he became unknown to younger generations. In 1962, he produced a compilation film of highlights from his old comedies titled "Harold Lloyd's World of Comedy", and another in 1963, "The Funny Side of Life". Both were well received and a new generation began discovering Lloyd. Harold Lloyd died in 1971 at the age of 77.

Beginning with the 1915 short film "Giving Them Fits", Lloyd's leading lady was actress Bebe Daniels. She appeared in just over 150 shorts with Lloyd and they became known as “The Girl” and “The Boy”, with a much publicized off-screen romance. Daniels was a big star but wanted to be a dramatic actress, and in 1919 she left Roach and Lloyd to work for Cecil B. DeMille. When looking to replace her, Roach spotted Mildred Davis in a small role in another film and suggested her to Lloyd who liked Davis and cast her in the 1919 comedy short “From Hand to Mouth”. The two would appear together in fifteen films. They fell in love and were married just after filming “Safety Last”. Though she made three more movies before retiring, this was her last film with Lloyd before becoming a full-time mother and wife. She and Lloyd had two children together and adopted a third. The Philadelphia-born Davis appeared in a total of 38 films including those with Lloyd. Her other notable films include "A Sailor-Made Man", "Grandma's Boy", "Dr. Jack", "Number, Please?", and her final, "Too Many Crooks”. Her marriage with Lloyd, which lasted from 1923 until her death, was the only marriage for each of them. Mildred Davis died in 1969 at the age of 68.

Many of the actors in small and bit parts in “Safety Last”, appear in many of Lloyd’s films, such as Noah Young, who plays "The Law" (the policeman chasing "Bill"). He appeared in over 50 films with Lloyd. There's also Anna Townsend who is billed as "The Grandma" (the tiny old woman buying fabric), who appeared in a few films with Lloyd, most famously as his grandmother in "Grandma's Boy".

One exception was Bill Strother who plays "The Pal”, “'Limpy' Bill". As mentioned previously, Strother was the "Human Spider" Lloyd saw scaling a building. While Strother's great in the film, he was not an actor and "Safety Last" was his only film appearance. When “The Law” chases “Bill” up the building, that’s Strother actually climbing the building.

This week’s classic film helped place comedy into the real world, with real people. It boasts a masterful combination of humor and stunts that will keep you laughing while on the edge of your seat. Enjoy a truly fun film, with one of silent cinema's great comedians and one of the most iconic scenes in all of cinema. Enjoy “Safety Last”!

This blog is a weekly series (currently biweekly) on all types of classic films from the silent era through the 1970s. It is designed to entertain and inform movie novices and lovers through watching one recommended classic film a week. The intent is that a love and deepened knowledge of cinema will evolve, along with a familiarity of important stars, directors, writers, the studio system, and a deeper understanding of cinema. I highly recommend visiting (or revisiting) the HOME page, which explains it all and provides a place where you can subscribe and get email notifications for every new post. Visit THE MOVIES page to see a list of all films currently on this site. Please leave comments, share this blog with family, friends, and on social media, and subscribe so you don’t miss a post. Thanks so much for reading!

YOU CAN STREAM OR BUY THE FILM HERE:

PLACES YOU CAN BUY THE FILM:

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases, and any and all money will go towards the fees for this blog. Thanks!!

TO READ AFTER VIEWING (contains spoilers):

There were no special effects in “Safety Last” and Harold Lloyd was indeed climbing up high on the top of buildings. Still dangerous enough to kill, his stunts were a bit safer than they appear. Eighteen-foot high sets were constructed replicating the front of the building and placed on the rooftops of different sized buildings in downtown Los Angeles (each one getting higher as “The Boy” climbed higher and higher). The sets were placed on the east sides of the roofs and were shot looking west. He was climbing on sets that were as high as fourteen stories above the street.

Platforms with mattresses were placed underneath, but it was still incredibly dangerous. When testing the platforms, they dropped a dummy from the set that weighed exactly what Lloyd weighed. It hit the mattress, bounced off, and dropped nine stories down to the street. If it was Lloyd, it would have meant instant death. Thankfully, that didn’t happen.

Lloyd wore the same rubber sole shoes worn by tightrope walkers. The climbing sequence took over two months to film. He was afraid of heights but said he got used to it as he kept filming. And remember, Lloyd did all climbing and stunts while missing a thumb and forefinger.

While Lloyd did almost all the stunts in his films, the extreme far shots of “The Boy” scaling the building were of Bill Strother acting as Lloyd’s double. Strother had a broken left leg while making this film and Lloyd insisted Strother be rigged with a wire, and though Strother objected, he did wear a wire when climbing up the building.

Davis on the other hand was so terrified of heights that for the shot where she embraces and kisses “The Boy” on the rooftop, two prop men were on the ground holding her ankles during the scene.

Comments